16 June 2022

Unpublished Letter to the Editor NZ Herald: There’s a Generational Change Starting, and We Need to Talk About It

As Patrick Gower recently led us through his personal journey from heavy drinker to sober and sensible (“On Booze” documentary and panel – TV3), there was little space for a deeper discussion of the actual facts about drinking in New Zealand. A quick examination of the official data tells us that the old Paddy was in the minority, and the new Paddy has joined the place where most of us already are.

Here are some of those facts from government sources –

- Between 80% and 90% of Kiwis already drink moderately and responsibly.[i]

- We’re drinking about 25% less per capita today than we did in the 1980s.[ii]

- Hazardous drinking has been on the decline over the same period.[iii]

- 82% of Kiwis drink at or below the Ministry of Health’s low-risk alcohol drinking advice.[iv]

- 92% of Kiwis have the recommended two (or more) alcohol-free days per week.

- Young adults are showing the rest of us the way with more and more drinking less or not at all.[v]

It’s not that we’re all perfect drinkers – far from it – there is still a lot of work to be done to shift the other Paddy’s out there into better drinking habits or not drinking at all. But there is definitely a generational shift happening in our drinking culture, and the real challenge is to figure out what’s fuelling it and accelerate the heck out of it.

Of course, there are some hints – the rise in the value of wellbeing, drinking no longer forming the centre of a social outing but as an adjunct to it, and being intoxicated increasingly being seen as unacceptable, antisocial behaviour. If we can create programmes that support these cultural changes, particularly with younger drinkers, then we’ll have a generation of parents modelling better drinking behaviours with their children. It’s a practical foundation because parents are still the greatest influencer on young people’s decisions around alcohol and how they end up drinking as adults.

As a nation, we are also becoming more conscious consumers; we’re changing what we drink and how we drink toward the ‘no, low, slow movement’, as seen through three responsible drinking trends:

- Embracing zero-alcohol beverages: It’s okay not to drink. 91% of Kiwis males wouldn’t care if a friend chose not to drink on a night out and 65% of us are comfortable not drinking on a night out.[vi]

- Low-alcohol beverages: 47% of Kiwis consumed low-alcohol drinks in the past year.

- Premiumisation: It’s more about quality than quantity. 56% of Kiwis are choosing premium beverages like craft beer, fine wine, spirits or cocktails to sip and savour slowly.[vii]

Public awareness campaigns and social change initiatives such as Cheers NZ and Alcohol&Me are also key to providing tools and information to help people better understand alcohol, how it affects them, what a standard drink is and why it is important to count your drinks, and ultimately help people make better decisions around alcohol.

But, conversations about changing our drinking culture by focusing on why things are improving and amplifying the parts that make a difference is not always a popular topic. A common narrative is to focus on broad-brush law changes to restrict or ban certain things that impact all drinkers, yet these fall well short of targeting those who drink harmfully.

That doesn’t mean changes to regulations are not needed, but to say we need to ban advertising, artificially hike prices, cut the number of alcohol licences and reduce hours will magically mean harmful drinkers will change their ways just doesn’t stack up. Sure, overall consumption may fall, but that’s because the reasonable consumer might choose to drink slightly less – not so much the harmful drinker.

When you look at it closely, since 1999, when our liquor laws were deregulated, the amount spent on advertising has gone up, we’ve gone from 3,000 to 11,000 on- and off-licences and trading hours have generally increased. Yet, we are drinking 25% less per capita. And, artificially increasing the price would be difficult to accept when you consider that Scotland has tried it but found in a recent extensive study that doing this had no impact on harmful drinking.

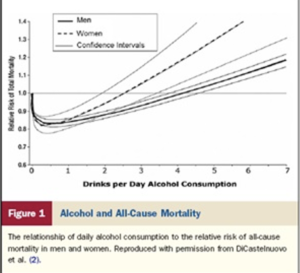

Misinformation and scaremongering will also do little to help facilitate positive change. The $7.8bn ‘cost of harm’ figure often quoted is simply inaccurate and has been discredited by independent economists because it omits any social, health or economic benefits and contains several key miscalculations.[viii] Ministry of Health data also shows that the areas of Auckland often cited as being the most egregiously impacted by alcohol actually have some of the lowest hazardous drinking rates in New Zealand.[ix] [x] Research also shows that all things being equal, light to moderate drinkers live longer than those who don’t drink at all because of the well-known cardiovascular benefits of sensible drinking.[xi]

Patrick Gower’s journey will inspire some Kiwis to make meaningful changes to their lives. Still, more widespread changes will never be achieved by banning advertising, increasing prices, reducing licenses, or removing alcohol from supermarkets. Change requires an all-of-society approach – central and local governments, healthcare and education providers, communities, families, individuals, and the alcohol industry – each playing their part and engaging in open, honest conversations. This needs to be underpinned by targeted education and campaigns to educate young people on alcohol-related harm, encourage moderate consumption, empower people with tools and information to make better decisions, and accessible support for those who need it.

ENDS

Need help?

Call the Alcohol Drug Helpline on 0800 787 797, free txt 8681, or visit alcoholdrughelp.org.nz.

Need more information? Here are some handy tips for better drinking decisions

- A good rule of thumb is ‘Go no, low or slow’. It’s okay to choose no- or low-alcohol drinks. If you choose to drink, pace yourself and enjoy your drink slowly.

- Check out org.nz and alcoholandme.org.nz for more information on what a standard drink is and how to make better drinking decisions.

- Get familiar with the Ministry of Health/Health Promotion Agency Te Hiringa Hauora Low-risk alcohol drinking advice to reduce your long-term health risks by drinking no more than:

- Two standard drinks a day for women and no more than 10 standard drinks a week,

- Three standard drinks a day for men and no more than 15 standard drinks a week,

- AND have at least two alcohol-free days every week.

[i] New Zealand Health Survey 2020/21, 19 November 2021, https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2020-21-new-zealand-health-survey Four in five adults (78.5%) drank alcohol in the past year. The majority (80.1%) are moderate drinkers and one in five drinking (19.9%) in a hazardous way. https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2020-21-annual-data-explorer/_w_fc7d32a5/#!/explore-indicators

The number of people who had a drink in the past year is declining, notably, adults aged 25-34 years (-4.8%), 45-54 years (-4.3%) and 65-74 years (-4.7%), and in the Māori population (-2.7%).

[ii] Decreasing alcohol consumption: StatsNZ Infoshare, Alcohol available for consumption to December 2021 (published 24 February 2022), https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/alcohol-available-for-consumption-year-ended-december-2021 and http://archive.stats.govt.nz/infoshare/ and https://teara.govt.nz/en/graph/40691/consumption-of-pure-alcohol-1960-2011 Alcohol available for consumption has been trending downward for a number of years. Data shows alcohol available for consumption was 8.734 litres per head of population (15 years and older) in December 2021. There has been a 27% decrease since 1978 when was 12.07 litres per head of population (15 years and older) and a 22.6% decrease since 1986 when there was 11.282 litres per head of population (15 years and older). Note: The per head of population (15 years and older) is the measure used by the OECD.

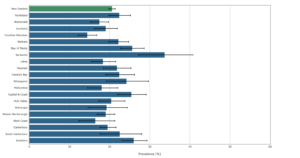

NZ consumption below OECD average: OECD Alcohol Consumption, https://data.oecd.org/healthrisk/alcohol-consumption.htm. Alcohol consumption is defined as annual sales of pure alcohol in litres per person aged 15 years and older. The OECD average consumption is 8.9 litres/capita (aged 15 and over). New Zealand is at 8.8 litres/capita vs UK 9.7 litres/capita. Source: OECD Health Statistics, 2019. New Zealand figures as at 2018.

[iii] New Zealand Health Survey 2020/21, 19 November 2021, https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2020-21-annual-data-explorer/_w_fc7d32a5/#!/explore-indicators

The survey also shows that hazardous drinking across the total population has declined slightly (-1.4%). It has decreased the most in the older generations: adults aged 35-44 years (-2.1%), 45-54 years (-4.2%), 65-74 years (-1.6%), and 75+ years (-1.7%). Hazardous drinking in the Māori population has also declined (-3.2%).

[iv] Alcohol Use in New Zealand Survey (AUiNZ) 2019/20 – High-level results 2019/20 (10 February 2021)

[v] New Zealand Health Survey 2020/21, 19 November 2021, https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2020-21-annual-data-explorer/_w_fc7d32a5/#!/explore-indicators

Younger adults are following global trends of drinking less. In young adults aged 18-24 years, the number of people drinking is down -2.8% from 89.1% in 2006/7 to 86.3% in 2020/21. This generation is more health and well-being conscious and looking for “better for me” beverage options that are no sugar, low-carb, or no- or low-alcohol.59.3% of young people aged 15-17 years had consumed alcohol in the past year, and this is a significant change (-15.2%) from 74.5% in 2006/7.Hazardous drinking across the total population has declined (-1.4%). Since first collecting the data on ‘hazardous drinking in the past year’ in 2015/16, there has been an overall reduction in people aged 18-24 years by -4.1%, those aged 25-34 years by -2.1%, and aged 35-44 years by -3.6%.[vi] Consumer research by 3Gem on behalf of Lion NZ, August 2021, sample size 1,000 New Zealanders aged 18-65 years.[vii] Consumer research: NZ Alcohol Beverages Council, New Zealander’s attitudes to alcohol research, December 2021, poll of 1500 New Zealanders undertaken by Curia Market Research.[viii] Dr Eric Crampton, NZ Initiative in Stuff, 23 August 2019 https://www.nzinitiative.org.nz/reports-and-media/opinion/dont-believe-the-hype-about-alcohols-multibillion-dollar-costDr Eric Crampton, NZ Initiative, Newsroom, 5 September 2018 https://www.nzinitiative.org.nz/reports-and-media/opinion/the-alcohol-cost-zombie-has-returned

[ix] Regional Results 2017-2020: New Zealand Health Survey (October 2021) The Ministry of Health recent regional Health Survey statistics shows despite Auckland being the most locked down region in 2020, regional data across the DHBs shows they had a lower prevalence for drinking alcohol in the past year (NZ average: 80.4%, Auckland: 77.8%, Waitemata: 77%, and Manukau-Counties: 69.2%, and lower prevalence for hazardous drinking in the past year (NZ average: 25.7%, Auckland: 24.4%, Waitemata: 22.7%, and Manukau-Counties: 20.9%) and were all under the national average. Counties-Manukau, actually has the lowest prevalence for hazardous drinking of all the regions in New Zealand.

[x] Regional Results 2017-2020: New Zealand Health Survey (October 2021)Hazardous drinkers (total population)

[xi] Global status report on alcohol and health 2018 https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565639

1.2.3.1 Cardiovascular diseases Numerous epidemiological studies have observed a complex relationship between both the volume and patterns of alcohol consumption and the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases (Roerecke & Rehm, 2012; Klatsky, 2015; O’Keefe et al., 2014). Specifically, volume and patterns of alcohol consumption have been shown to increase the risk of hypertensive heart disease (Taylor et al., 2009; Briasoulis, Agarwal & Messerli, 2012), cardiomyopathy (Lacovoni, De Maria & Gavazzi, 2010), atrial fibrillation and flutter (Kodama et al., 2011), and haemorrhagic and other non-ischaemic strokes (Patra et al., 2010). The relationship between alcohol and the onset of ischaemic heart disease or ischaemic strokes is complex; people who consume low-to-moderate amounts of alcohol and do not engage in irregular heavy drinking have a lower disease risk, while people who engage in irregular heavy drinking or who consume higher volumes of alcohol have a higher disease risk (Roerecke & Rehm, 2010; Leong et al., 2014; Guiraud et al., 2010; Roerecke & Rehm, 2014).

[xi] Alcohol dosing and total mortality in men and women: an updated meta-analysis of 34 prospective studies. Di Castelnuovo A1, Costanzo S, Bagnardi V, Donati MB, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G.: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17159008 Decades of epidemiology have shown that the relationship between alcohol consumption and mortality is J-shaped. At moderate rates of consumption, mortality risk falls below that of a teetotaler/abstainer and then rises, exceeding that of a teetotaler at around 30-40 units per week. The exact shape of the curve varies depending on your criteria for inclusion, but the basic conclusion is always the same: moderate drinkers live longer than teetotalers.